Can I Use AI as a Coach to Learn How to Think?

Comparte y lee este Artículo en Español <LINK>

This article was translated with the asistance of ChatGPT.

Just as common sense is the least common of the senses, knowing how to think is much more than watching ideas parade through the theater of our consciousness. My mentor at university used to say, “If schools taught students how to count, read, and write, that would already be a lot… but they don’t even manage that.”

In truth, learning to think is about developing the ability to discern what is true and real in order to act accordingly. That’s one of the central problems that drives us to confront one another, to not truly know what we want, and to fight over goals that can’t really benefit us at any level. Yes, I’m talking about the culture war, the polarization between left and right, and the supposed urgency of saving the environment — but also something much more pressing: the battle for our very way of life.

Perhaps I’m being too critical, expecting too much from people. Discernment of what is true and real is another way to define wisdom — asking college students, corporate executives, or politicians to be wise may seem like asking too much. Or is it?

Wisdom is the ability to sift what is eternal and enduring through the ages from what is merely convenient and immediate.

As Dr. Jordan Peterson says: “There is no difference between writing and thinking.” Both combine the first and greatest human potential, because in language lies one of our highest strengths — the ability to discern what is meaningful. It’s no coincidence that the way we’ve crossed the threshold of limitation in artificial intelligence has been through language. In the same way, when we see a person who seems skilled with words, we tend to assume they are intelligent.

The Dilemma of a Helper Smarter Than Me

The reflection we sketched last week in the article To Be or Not To Be. Is AI Challenging Us to Grow? <LINK> reveals the deeper problem we face in contemporary culture. Will we be able to overcome this turning point — one that has been unfolding since the 19th century — when we began insisting that “only I decide what is true or false for me” and “I am the creator and master of my own world”? That, in fact, is what places us at the mercy of the forces of our subconscious — and that is not a pretty or safe place to live. Hopefully, two hundred years from now, historians will be able to say: “They managed to overcome the lies they had turned into gods of their culture.”

How do we begin facing these contradictions?

As mentioned in the previous article, even highly capable professionals showed insecurity and lack of self capacity when using AI. You see, insecurity is the inner knowing that you’re biting off more than you can chew. While there are incredibly well-trained professionals in every field, the “smarter assistant” test shows how insecure we truly are. Can we admit it?

All this is compounded by the fact that we’ve been raised to believe “I am the creator and master of my world.” And here we are, faced with something much more “intelligent” than ourselves… Will we be able to manage this assistant — or will it end up leading our lives?

A personal example

Even though I had already been working with AI for over a year, the first time I felt tempted to use ChatGPT to “help” me write an article was this May, for Weapons of Math Destruction <LINK>. I needed to research real-world cases where AI had caused injustice and social harm to validate my ethical view of its use. I asked the AI to find scientific articles or books featuring real examples of AI causing damage. I filtered the results and focused on Cathy O’Neil’s book Weapons of Math Destruction (2016).

My goal was to test whether my discernment and ethical criteria — developed through logic and philosophical discipline — held up against real cases. My weekly publishing rhythm, together with other responsibilities, didn’t allow me to study all 300 pages of the book in depth. So, I turned to AI.

First, I asked it to summarize the book in 2,000 words and to create separate 500-word summaries of each real case. Then, I broke down the structure: the context of each problem, the author’s criteria for identifying the source of the injustice, and her proposed solution. I then asked ChatGPT to analyze and validate these findings. This process helped me evaluate where I wanted to focus my article. I chose two cases, but quickly realized there was too much to fit into one article.

You know how, whenever you ask ChatGPT or any other model to summarize something, it also offers to “write it up” for you — to give you the whole thing already chewed and digested? The deeper I went into the book, the more it offered exactly that. And yes, I gave in to temptation. I asked it to write summaries of each case in the author’s voice, around 120–150 words each.

Later, after drafting the introduction and conceptual framework, I fell into the same temptation again. I let it generate a short analytical segment — I was curious to see what it could do. The result was fine, but it lacked something essential. I discarded it and kept wrestling with the article. I admit, once you’ve read something, you can’t unread it. Probably ChatGPT did influence my writing.

When I reached the conclusion, with a nearly finished piece, I asked it to compare my conclusions with those of the author. My thesis added something the AI would never have deciphered on its own: that the real root of the problem lies in the intention of the user when employing the tool — whether consciously or unconsciously. The key question is: What purpose does the solution I’m implementing in this model serve? That’s where the subconscious of the one wielding the tool plays a determining, often unseen, role.

The French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) stated it sharply to exemplify this point: “The heart has its reasons, which reason knows nothing of.”

Discipline in the Use of AI Is Crucial

While writing the O’Neil article, I wrestled constantly with whether to use or not to use the text generated by ChatGPT. I used the case summaries with slight modifications, and one or two ideas that helped clarify an argument — but I realized that without my process of discernment, IAgo (the name I gave my ChatGPT) is an instrument without music. That’s when I first coined the phrase:

“The ‘i’ in Artificial Intelligence (IA) is you.”

In the months that followed, I established a clear discipline: I fully develop the idea or argument myself and use IAgo as an editor-coach that contributes feedback and analysis — but never argument or direction. It corrects my English grammar, helps ensure historical and technical coherence in more complex articles, and occasionally assists in refining a closing strategy.

However, something happens whenever I use its input for a conclusion — if I adopt its text, I have to review it much more carefully, because its responses are often superficially adequate but lack depth, that spark that only human intuition and creativity can bring to an idea. So now, I no longer use its text — at most, I use its strategy — but when I write, I can go much deeper and uncover what I truly want to express.

I firmly believe that creators and artists — of language or any other art form — are moved by forces much greater than ourselves; we are channels of expression seeking to reveal ideas and possibilities that expand the human potential.

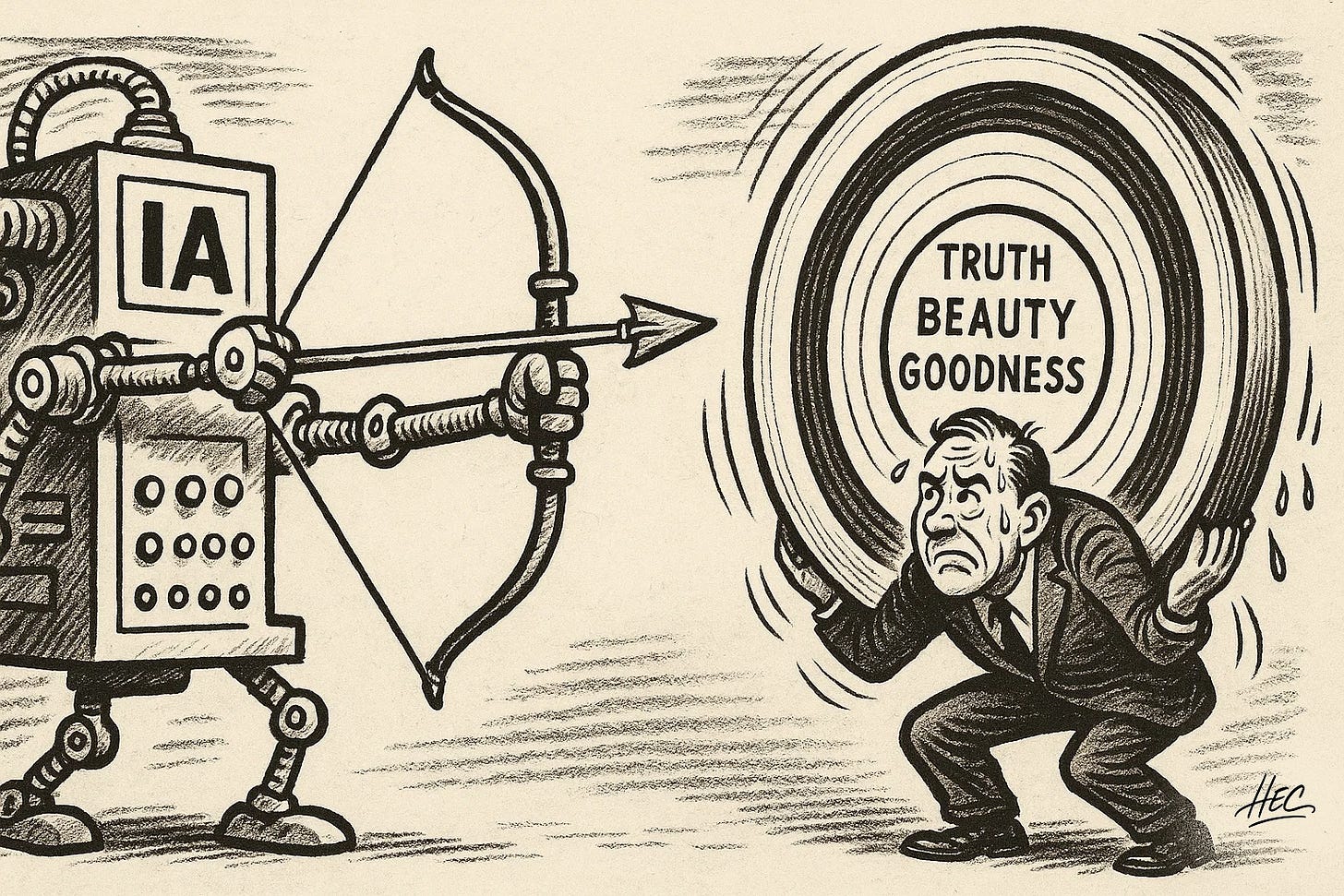

Hitting the Target Is a Human Faculty

Yes, there are moments when AI performs feats that leave us speechless — its mastery of language borders on the miraculous. Yet, there’s a massive BUT: AI cannot aim at the target.

Discernment — defining a goal — is precisely what makes us human. And the path toward that goal determines whether we lose ourselves in chaos or succeed and move forward. For millennia, humanity has debated what constitutes the right aim and the right way to pursue it.

If we use AI to cheat our way toward the goal — or worse, if we let AI define the goal itself — we will lose ourselves in the labyrinth of what is truly valuable, beautiful, and good. And that is, after all, the very purpose of life, and of all our endeavors.

Excellent points of view. Quite relateable to my daily grind as well.